The Afghan Australian story is a remarkable tale of identity, resilience, adaptation, and the enduring human quest for belonging.

From the arrival of the first cameleers in the 1860s to today’s vibrant Afghan Australian communities, this is an endearing relationship which spans more than 150 years.

Through cultural negotiation, transformation, and connection, this also the story of the Afghani Cameleers.

Rough Beginnings: The Cameleers’ Arrival and Identity Formation

After the infamous Burke and Wills expedition, and at the bequest of Thomas Elder, the first Afghan cameleers arrived in Australia around 1860.

This country was tough back then. And it’s still tough now. But prior to mechanised transport, crossing through the more arid regions of the Australian interior simply was not possible on horseback.

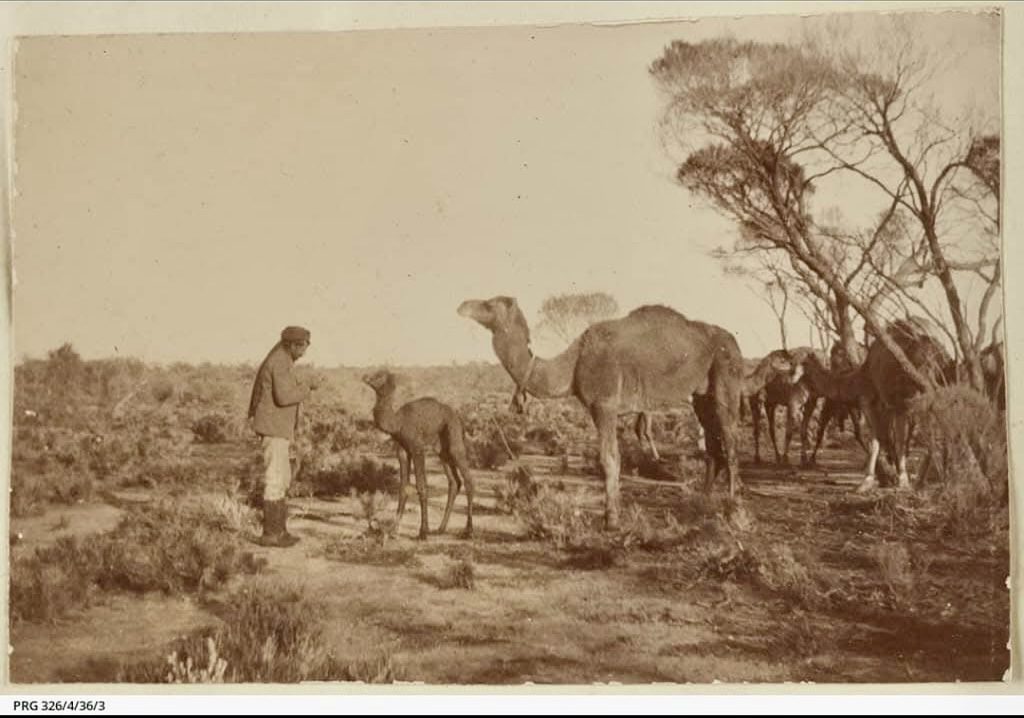

Camels, and their handlers presented pioneers and early explorers with the perfect solution.

These handlers—affectionately known as the Afghani Cameleers brought with them not only expert camel-handling skills. They also brought with them their own rich cultural and religious traditions.

But although they collectively called: Afghani, many came from regions of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India.

It was an early identity shaped by occupation role, faith, regional origins, and colonial objectification.

Initially, many cameleers believed their stay would only be temporary. So, they decided to keep strong ties to their homelands through language, religion, and customs.

To the cameleers, such religious practices were vital to their identity. They set up Australia’s first mosques, such as the Adelaide Mosque (1888). And the Broken Hill Mosque (1891). Each serving as hubs for worship, education, and communal support.

Despite the challenges of life in a foreign land, they practised their rituals faithfully. They integrated prayer and fasting into their demanding work routines. But, at the same time, practical realities led to cultural adaptations.

The cameleers developed a unique pidgin language blending English with Pashto, Dari, and other languages. They adapted clothing for the Australian climate and modified religious practices pragmatically.

Their interactions with Aboriginal communities often led to intercultural marriages. This created families with blended Afghan, Aboriginal, and European heritages.

These early multicultural—although not considered legal, let alone accepted at the time—navigated complex identity negotiations long before multiculturalism became official Australian policy.

Challenges and Decline: The Impact of the White Australia Policy

The introduction of the White Australia Policy in 1901 marked a turning point in the cameleer story.

Immigration restrictions prevented new arrivals, separated families (many cameleers travelled to Australia, alone, and were forced to leave their wives and children in their home country). But it also denied citizenship to the Afghani cameleers… despite their contributions to the nation’s development.

This official exclusion fostered feelings of rejection and led to a devastating marginalisation of the cameleers.

Then came the great technological advancements of the 20th century.

The introduction of the motor vehicle meant that camels were replaced. This further diminished the community’s visibility and economic niche.

Many cameleers, and their Australian offspring dispersed into urban areas, and cultural transmission weakened.

Some families concealed their heritage to avoid discrimination, while others kept private their cultural and religious practices alive.

This period created dormant identities, where Afghan heritage was preserved quietly but not publicly expressed.

Preserving Heritage: Memory Keepers and Cultural Continuity

Despite these challenges, certain individuals and families became memory keepers, safeguarding cultural knowledge through family histories, religious practice, language, and preservation of artefacts. Nowadays, efforts to support the historic mosques and gravesites help to anchor the community’s heritage.

These acts of preservation laid the groundwork for later cultural revival and reconnection.

Revival and Renewal: Multiculturalism and New Waves of Immigration

Australia made the shift to multicultural policies in the 1970s (White Australia policy did not end until 1973). This opened new opportunities for Afghan Australians to reclaim and celebrate their identity. Heritage associations, oral history projects, cultural festivals, and restoration of historic sites became important avenues for expressing the Afghan Australian culture.

Simultaneously, new waves of Afghan immigrants arrived.

Many new Afghan Australians were fleeing Soviet invasion, civil war, Taliban oppression, and ongoing conflicts. They also revitalised the community with renewed language use, religious participation, cultural institutions, and new businesses.

For descendants, like me, these arrivals offered a chance to reconnect with traditions that had all but been erased over the past half century.

Navigating Complex Identities in Contemporary Australia

Today, Afghan Australians embody multiple identities, balancing Afghan and Australian national affiliations, religious and secular life with traditional and modern cultural practices.

Many embrace the Afghan Australian identity, selectively keeping traditions compatible with Australian society while innovating new cultural expressions.

However, September 11 posed a new set of challenges.

Increased xenophobia, societal scrutiny and discrimination, tested the community’s resilience.

In response, Afghan Australians engaged in interfaith dialogue, media outreach, education, political participation, and internal support networks.

The recognition of the historic cameleer contribution also helped counter negative stereotypes by highlighting a long-standing Afghan presence in Australia.

Digital Connections and Transnational Belonging

The digital age has transformed Afghan Australian identity and enabled immediate access to homeland media, global diaspora networks, and cultural resources.

Social media platforms help identity expression and intergenerational connection, bridging descendants of early cameleers with recent arrivals.

This digital engagement fosters a transnational identity that transcends geographic and social boundaries.

Discovering Hidden Heritage: Genealogy and Identity Reconstruction

A growing number of Australians are discovering Afghan ancestry through genealogical research and DNA testing facilities, such as Ancestry.com.

These revelations often prompt profound personal reflection and identity reconstruction. Many experience surprise, curiosity, and a desire to learn about Afghan history, culture, and religion.

This process of cultural recovery involves acquiring new learnings, adopting meaningful practices, connecting with community, and revising family narratives, while psychologists note that gradual, thoughtful engagement supports healthy identity integration, offering psychological benefits such as coherence, belonging, resilience, and new meaning.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Evolution of Afghan Australian Identity

The Afghan Australian experience illustrates the dynamic nature of cultural identity.

The culture expresses itself as both resilient and adaptable, and rooted but always evolving.

From pioneering cameleers setting up Australia’s first mosques to contemporary communities navigating complex multicultural realities, Afghan Australians prove how multiple cultural belongings can coexist and enrich lives.

Their history challenges simplistic notions of identity as fixed or singular, showing instead how heritage can be a resource for psychological well-being and social participation.

As Australia continues to embrace diversity, the Afghan Australian story offers valuable lessons about inclusion, cultural innovation, and the power of belonging.